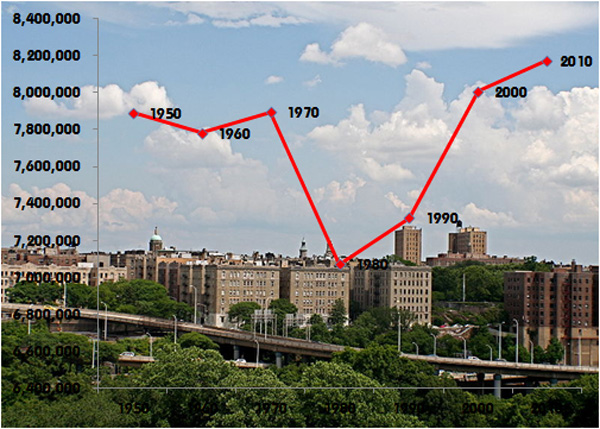

Photo by: Asaavedra32; Data from NYC Dept. of Planning

New York City’s population loss in the 1970s reversed in the 1980s, thanks in part to immigrant newcomers who populated areas like Washington Heights.

The Census bureau had a surprise for New Yorkers in late August 1990. Despite the economic boom of the preceding decade and neighborhoods that seemed to be bursting at the seams with new arrivals, the bureau announced that it had counted 7,033,179 New Yorkers, some 40,000 fewer than it had found ten years before.

Mayor David Dinkins called the number “unadulterated nonsense.” Governor Mario Cuomo claimed the Republican administration in Washington was deliberately trying to erode Democratic seats in Congress. Demographer Emanuel Tobier of New York University pointed to a 28 percent increase in births in the city in the last decade. “It is inconceivable to me that this type of increase could take place without an increase in the population,” he said.

Five months later, the Census Bureau admitted that it had failed to do a good job counting people in cities, especially in New York, and revised its figure up to 7,322,564. While city officials continued to insist that some 300,000 people had still been missed, the revision represented a historic milestone. The increase of 3.5 percent closed the chapter on the disastrous decade of the 1970s, when the population had declined by about 800,000 people. The new count also made New York one of the few urban areas in the Northeast or Midwest to see its population grow.

Demographers all pointed to the same reason for the city’s resurgence—immigration was reshaping New York. In 1970, the number of foreign-born New Yorkers had declined to just over 1.4 million, or only 18 percent of the population, the lowest figure in the century. Now more than 2 million residents had been born elsewhere, 28 percent of the total. Without the surge in immigration, New York’s population in the 1980s would have declined by another 9 percent instead of growing. New York would have been on the road to the kind of city Detroit became. “Is there anything wrong with a city of 5 million?” asked Lou Winnick, who had studied the role of immigration for many years. “No. But a city that goes from 8 million to 5 million—there would be cobwebs all over.”

Instead of abandoned blocks, neighborhoods were repopulated by the immigrants, who first crowded into existing housing stock and then invested to improve it. The new arrivals reinvigorated the local economies where they lived. They provided the manpower to bolster the city’s key industries; after all, the primary reason they came was for the economic opportunities the city offered. And while New York became known as an immigrant-friendly city, it achieved that reputation only after a decade of conflict.

New York’s good fortune resulted from the landmark 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which replaced the national quota system imposed in the 1920s. The 1920s law not only limited the number of immigrants, it favored Western European nations where there was little interest in coming to the United States. The 1965 reform eliminated those quotas and opened the country to the rest of the world by creating four pathways: immigrants could be reunited with other family members, they could come to fill the need for specific jobs, they could qualify under a program designed to diversify the countries of origin, or they could claim refugee status.

This dramatically affected the nationalities of the immigrants who flocked to New York. In 1970, Italy was the largest source of foreign- born New Yorkers, followed by Poland, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Ireland. In 1990, the Dominican Republic was by far the largest source of immigrants, followed by China, Jamaica, Italy, and the Soviet Union. Washington Heights in northern Manhattan, where many Dominicans decided to settle, was one of the first areas to show the enormous benefits that immigrants brought to the city.

Named for Fort Washington, constructed by the Continental Army in its vain effort to hold New York during the Revolutionary War, the neighborhood was most well-known for the George Washington Bridge, the busiest motor vehicle span in the world. The neighborhood had long been a destination for new arrivals—the Irish in the 1900s, European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s, and Greeks in the 1950s and 1960s. Dominicans came because conditions on their homeland were so dismal—the average salary in the early 1990s was $40 a month—and often took jobs in the city’s service industries, such as driving livery cabs. Some became business owners and bought out the Puerto Ricans who owned bodegas that supplied food and other necessities to poor neighborhoods. The Dominicans could afford to send somewhere between $300 million and $600 million a year back to their homeland in the early 1990s, second only to tourism in economic impact on the country.

This success story received little attention. Instead, Dominicans soon came to be associated with the crack-cocaine drug epidemic sweeping the city. Part of the problem was the bridge, which allowed suburbanites to easily enter the city, buy drugs, and make a quick getaway. Another problem was corrupt cops, who allowed the activity to flourish so they could rob the dealers and make some sales themselves with the drugs they stole. Violence engulfed the neighborhood. In 1990, the 34th Precinct, which included Washington Heights, accounted for 103 murders, the second highest in the city.

The corrupt police officers were arrested in the early months of the Giuliani administration, and the Bratton tactics eventually made the neighborhood safe again. The stigma faded, and the presence of Dominicans spread throughout New York, fitting for the largest immigrant group in the city.

The impact in Queens was even more pronounced, especially in Flushing, the last stop on the No. 7 subway line, which became known as the International Express. Originating in Times Square, the 7 train’s Queensboro Plaza stop was adjacent to the Greek and Italian communities of Astoria; then it reached Sunnyside, a neighborhood populated by Koreans and Colombians; Jackson Heights followed, a South American enclave led by Colombians; and it ended in Flushing, where Taiwanese Chinese and other Asians created one of the most thriving areas of the city—and sparked resentment for their success.

From Modern New York by Greg David. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers, Ltd.