City & State

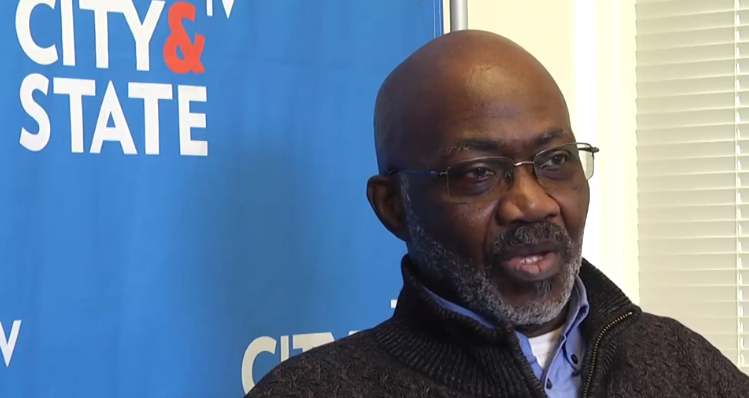

CASA organizer Fitzroy Christian.

The Bronxites who live and work around Jerome Avenue in the Southwest Bronx are familiar with at least one side of the Tale of Two Cities.

Community District 5, which covers the northern portion of the Jerome Avenue corridor being studied by the Department of City Planning for possible development under the city’s affordable housing plan, has a poverty rate double the citywide average. It is home to more people paying 50 percent or more of their income in rent than any other district in New York. On the southern end of the corridor, District 4 is the fourth poorest in the city and boasts the second-highest level of unemployment.

So when word came that the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio, elected on a promise to close the gap between the city of haves and the city of have-nots, was looking at the area to play a key role in his plan to preserve or build 200,000 units of affordable housing, one might expect Jerome-area residents to be excited.

The reality, explained Fitzroy Christian, is more complicated.

“[It] may sound kind of weird, but it was a good plan that I was very much afraid of,” said Christian, an organizer with Community Action for Safe Apartments or CASA, a project of New Settlement Apartments, which develops housing in the area.

“We understand that the South Bronx in particular has been a neglected area for a very very long time. The previous administrations had virtually disinvested in that area of New York City. We were—even more than Staten Island—the forgotten borough,” he explained during a March 11 video interview with City & State. “So, yes, hearing that the mayor wanted to include our area of the Bronx in his plan to preserve and build 200,000 apartments for low-income people was exciting. It means that at last we are being looked at as people who are deserving of some of the riches of New York City.”

But the excitement was tempered by distrust over how other development efforts facilitated by City Planning, along Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn for instance, had ended up. “We saw where people were promised that there was not going to be displace, that there was not going to be discrimination against or any harassments against the present tenants and that most of them were going to be able to remain where they are. We saw that that wasn’t true.”

Christian echoes a sentiment heard elsewhere in the city, particularly in East New York, another area the administration has focused on for the mayor’s housing plan. The legacy of Bloomberg-era rezonings—in Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Harlem and elsewhere—has made community organizations very skeptical of even the best intentions. It didn’t help, Christian notes, that City Planning began studying the area months before it engaged the community to find out what residents and businesses want.

City Planning has taken steps to address the distrust, both in how it approaches the community and in how it approaches its own job. In recent months, the agency has organized walking tours, publicized meetings sponsored by outside groups to discuss the potential plans, and released more of its information in Spanish—all modest steps but major departures from how the department did business under Mayor Bloomberg. More importantly, the agency says it is looking more holistically at what neighborhoods want and need. Rather than simply offering a rezoning—which essentially paves the way for the private sector to remake an area in its own vision—the department says it will use its new influence over the city’s capital budget to coordinate public investments in parks, streets and schools in order to address local demand and reduce the strains that new, private development place on existing resources.

The city’s efforts even extend to nomenclature: The agency is careful not to refer to a “proposal” or “plan” for the area around Jerome Avenue, instead calling it a “process.” And when groups like CASA balked at the department’s labeling of the area as “Cromwell-Jerome”—a neighborhood name that was new to people who’d spent their lives there—the agency scrapped it for the current “Jerome Avenue corridor.”

Christian acknowledges that City Planning has made an effort to listen, but he remains uncertain about what will come of the outreach, “Whether they are going to be presenting the plans and just asking for wider participation and ‘Do you like it?’ and ‘Let’s tweak it a little bit,'” or if it is going to be a real visioning meeting where residents and small business owners are asked, “‘What are your ideas? What can we do to make sure that your history, your traditions there, are preserved as much as possible while we upgrade it?'”

Already, says Christian, auto-related businesses along Jerome Avenue are reporting that they aren’t being offered renewal leases or are facing rent hikes of 300 percent or more. Change is inevitable, he says, “But if it’s going to be accelerated by city input, we would like it so that what we have our traditions remain as intact as possible while those who are coming in to join us will bring added flavor to it.”

Whatever process or proposal or plan emerges for the area around Jerome Avenue, he adds, “We are hoping that we can be a part of it.”

City Limits coverage of the Bronx is supported by the New York Community Trust.

One thought on “Fear of City’s ‘Good Plan’ for Housing”

Pingback: Urban Omnibus » “The scythe of progress must move northward”: Urban Renewal on the Upper West Side