Photo by: Jarrett Murphy/WHO

The illegal market for HIV medication might be fueled by demand from abroad, especially in the Caribbean, where a large segment of the HIV population in countries like Haiti and the Dominican Republican has no access to life-saving drugs.

Three months ago, Ms Cruz’s doctor warned her about the abnormal level of T-cells in her blood. They had reached such a low level that the slender 46-year-old Bronx resident was about to shift from being HIV-positive to having full-blown AIDS. So Cruz made an instantaneous decision—to stop selling her HIV drugs on the black market to support her 20-year cocaine addiction. Now, she realizes, she had been toying with a death sentence.

Homeless and unemployed, the mother of six is one of the nearly 109,000 New Yorkers who are living with HIV or AIDS. Their expensive array of medications has become particularly popular on the black-market in the past couple of years, according to law enforcement sources.

Drug users like Cruz are the main providers of HIV pills such as Atripla or Videx on the street, sources say. But others make the difficult choice to sell their pills not to buy drugs but to pay their rent.

So far, this kind of drug dealing has not been punished harshly by the judicial system. With no prior criminal record, a dealer caught selling $1,000-worth of prescription drugs could be sentenced to one to four years in prison, but most likely would receive probation or a shorter sentence, explains Tom Tapp, chief of the Bronx District Attorney’s Arson and Economic Crime Bureau, which prosecutes Medicaid fraud and other abuses related to prescription drugs. For a sale involving a similar amount of money, a dealer selling narcotics such as crack or cocaine could get up to nine years in jail.

But a bill sponsored by New York Sen. Kemp Hannon and passed by the Senate in June could close that gap if approved by the assembly this year.

The bill identified an “exploding black market in non-controlled substance medications,” including AIDS medications that are either sold to pharmacies or shipped overseas. Under the bill, first degree “criminal diversion of prescription medications and prescriptions” moves from a C felony (with likely maximum jail time of five to 15 years) to a B felony, for which the maximum is eight to 25 years.

Indeed, law enforcement officials suspect that demand for HIV drugs in foreign countries fuels the trade in HIV medication.

“What I know is anecdotal, I don’t have any data,” says Tapp. “But they are often sent overseas because medications aren’t available, like in Dominican Republic.”

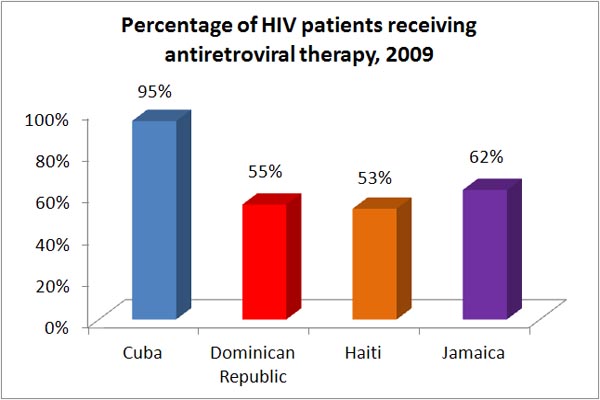

The incentive for access to these drugs is acute. According to a 2011 report from the World Health Organization at least 45 percent of the HIV/AIDS population in the Dominican Republic had no access to appropriate treatment in 2009. In Haiti, 47 percent of people needing antiretroviral drugs didn’t get them, and in Jamaica some 38 percent did not. In Cuba, fewer than 5 percent of HIV patients went without meds.

Law enforcement experts report that Washington Heights has become the heart of the illegal HIV drug traffic.

Last September, Assemblyman Herman D. Farrell, Jr, City Councilman Ydanis Rodriguez and the Manhattan district attorney, Cyrus R. Vance, Jr. gathered at the 33rd Precinct in Washington Heights to discuss the possible new legislation toughening sanctions on prescription and medication dealers.

A new drug threat

“There’s always been a significant drug problem in the area,” says Michael Mowatt-Wynn, president of the 33rd Precinct’s Community Council for 10 years. Mowatt-Wynn, who also lives in the neighborhood, says Washington Heights has a history of gang and drug problems. The area was one of the first “model blocks,” a 1999 city initiative that aimed at reducing illegal drug activity by increasing police presence. The experiment was seen as a success as crime quickly dropped by 20 percent.

But Mowatt-Wynn says that five or six years ago he first started noticing the unusual business inside the 157th Street subway station on the number 1 train.

“We’re facing a completely different situation than the usual crack, cocaine, marijuana,” says Mowatt-Wynn, who runs the Harlem & the Heights Historical Society.

“On 157th Street at the top of the stairs, there are between two and five Hispanic young men searching the crowds and people coming up the stairs,” says Mowatt-Wynn, adding that he was once approached himself by the men.

They’re looking for people who could be coming out of the pharmacy with medications, carrying plastic bags. With a simple nod of the head, one of the men will go down the stairs and, in full view of passers-by, exchange the bag for cash. But according to Mowatt-Wynn, the transactions became too obvious, so the buyers now escort the seller to a nearby street corner.

Two major arrests by the Drug Enforcement Administration dismantled two drug rings last year. One was in Brooklyn and involved a bodega owner and a couple who were shipping the HIV medication to the Dominican Republic. The other arrest took place in Yonkers, where DEA agents seized 6,500 bottles of pills worth $4.23 million. According to the DEA, many of the bottles were the kinds of medications used to treat people with HIV.

The police placed cameras at the top of the stairs of the 157th Street subway stop and have been monitoring the deals made there. But according to some, the lack of stricter penalties is hurting local police efforts to target street buyers and sellers in the streets. “The only thing they can go for is Medicaid fraud, but that is if they catch the pharmacist buying,” says Mowatt-Wynn.

One thought on “Sales of HIV Meds Catch Lawmakers' Eyes”

My name is Google voice Hines and I have lived in New York City for 25 years I have been reporting this videotaping every drug sale and I was the one that reported this to the Attorney General in 2019 I have been campaigning like a mad dog about the sale of HIV aids drugs on the streets of New York City and every other major city around the United States I have been going crazy these past three weeks trying to talk to lawmakers that refuse to listen to me listen ladies and gentlemen I lived at 157 Broadway. I am in North Carolina right now and I plan to go to the streets of Washington Heights starting February 4 with a bull horn and I am going to blast every person that comes down that street with my bull horn and say no longer will I sit by and except drug dealers foreigners from other countries buying HIV aids medication‘s from our black and white brown and blue citizens of all nationalities and all religions no longer after 27 years of age and I got a watch my friends that have addictions like at Riverpark towers get on that bus and go to Washington Heights and sell their drugs I know the ins and outs about it and trust me I’m coming for you or either you’ll shoot me dead on the streets to you drug dealers and to you vicious heinous bastards make you burn and rot in hell not only are you causing the person that you’re buying the drugs from to die but you’re also allowing the spread of HIV and aids you better come for me my name is Google voice Hines I live at Riverpark towers if you wanna rumble let’s rumble cause I’m gonna blow your operation away step-by-step voice by voice I’m taken to the streets with my people and there’s more of us than you drug dealers you lowlife bastards you