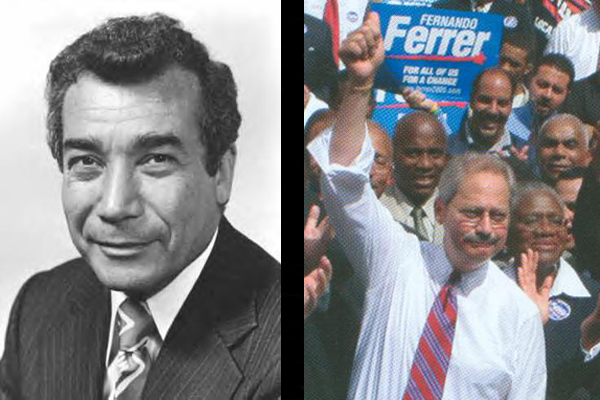

Photo by: Library of Congress, Ferrer 2005

Herman Badillo, seen at left, as a congressman in the 1970s, was also a Bronx borough president and ran for mayor six times, never securing a party nomination. Councilman, borough president and three-time mayoral hopeful Fernando “Freddy” Ferrer was the first Latino to win the nomination of a major party for City Hall. But his achievement in 2005 was dwarfed by the magnitude of his loss to the popular—and financially limitless—incumbent Mayor Bloomberg.

While the Latino population in New York has become greatly diversified over the last 20 years, the heart of Latino political power in the city remains tied to its still-dominant demographic group, Puerto Ricans. It can be said that Latinos first got on the political map during the rise to power In the 1930s and ‘40s of Italian-American U.S. Representative Vito Marcantonio, who, despite being a Republican, was a Communist and Socialist sympathizer. His constituency in East Harlem included many Puerto Rican migrants; he was perhaps the first politician to display and ability to rally their support and project their interests

Marcantonio’s decline in influence among both New Yorkers and Puerto Ricans had to do with the decline of leftist ideology during the Cold War, at least among elected officials. At the same time, some of the forces that made Puerto Ricans an emerging population—like the successful organization of tobacco workers and the need for cheap industrial labor—fell apart in the 1950s, when Puerto Rican workers became expendable. The public perception of Puerto Ricans was also soured by increasingly stereotyped depictions in the media and the emergence of street gangs. The community began to organize locally around leaders like Antonio Pantoja, founder of the Puerto Rican empowerment group Aspira, and then later radical political groups like the Young Lords, to assert their rights during the Civil Rights Era and the tumultuous 1960s.

When I was growing up in the Bronx, the first leader to step into this charged atmosphere and play a significant role in the world of electoral politics of the Puerto Rican community was Herman Badillo. First as borough president of the Bronx, where he was elected in 1965, and then as a four-term U.S. Representative, Badillo was in a sense ahead of his time, combining an unusually strong ability to communicate in relatively unaccented English and a medium-dark complexion that distinguished him from the lighter-skinned Puerto Rican elite. He was an authentic Everyman with a smooth air of sophistication that played well during the liberal John Lindsay era.

Trial and errors

His first attempt at running for mayor was in 1969 against the Republican Lindsay, when he declined a spot on the ticket of former Democratic Mayor Robert Wagner (attempting a comeback after four years in retirement) and decided to run himself, finishing a respectable third behind nominee Mario Procaccino and Wagner. He would run four more times, at one point giving up his House seat to become deputy mayor under Ed Koch after his unsuccessful run in 1977.

1969 Democratic Mayoral Primary:

Badillo’s First Try

But it was his disastrous inability to come to terms with the African-American political power base in Harlem that marred his last viable run, in 1985. Badillo worked hard to earn the support of what was then called the Coalition for a Just New York, the Harlem power bloc, led by Borough President Percy Sutton. But his run was complicated by the candidacy of East Harlem Councilman Angelo Del Toro, who announced he wanted the City Council presidency. Not only was Del Toro associated with significant patronage scandals, but the African-American bloc did not want to endorse a Latino for both mayor and city council president. Instead, the group Badillo would derisively call the “Gang of Four” (referring to Sutton, Dinkins, Congressman Charles Rangel, and prominent attorney Basil Patterson (father of the recent governor) announced that it would give its endorsement to the undistinguished candidacy of Herman “Denny Farrell.

“In ’69 and ’73 he did very well in putting together a black-Latino coalition,” says Ferrer, acknowledging Badillo’s strong showing among black voters as well. “It was in ’77 where it began to fall apart and in ’85 the African-American community came up with their own candidates. I think the emergence of their own candidates sort of changed the variables.”

1973 Democratic Mayoral Primary:

Badillo’s Best Shot

Badillo’s inability to play nice with the Harlem African-American club may have stemmed from the fact that his unpredictable early success had created credible candidacies for Latinos before African Americans did. Beyond that, his persona reflected a short-lived notion that Puerto Ricans were considered as candidates for ethnic succession—in other words, that like Irish and Italians before them, they were just the latest wave of “ethnic” candidates. This meant that as “Hispanics,” Puerto Ricans and other Latinos could find a place in the melting pot as hyphenated Americans with some ties to European ethnicity, in part because they were strongly Catholic (although Badillo himself was Baptist). But during the period of Badillo’s ascendancy, a new generation was creating a different idea about identity and politics.

“Badillo’s failure to establish a black and Latino coalition is part and parcel of his arrogance and lack of attention to why he had become a respected and noted political leader,” says LIU politics professor José Sánchez. “He simply assumed that it was because of his brilliance and his eloquence and his attention to detail, and so he didn’t pay enough attention to the fact that he was simply riding a wave.”

1973 Democratic Mayoral Runoff:

Hopes Dashed

Sánchez suggested that Badillo’s early success put him out of touch with the nationalist movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s that were creating a new kind of minority politics. “Badillo failed to recognize his power wasn’t coming from the Democratic Party, it wasn’t coming from the white working class. It was coming from the emerging oppositional culture of Latinos and African-Americans, and that’s why he all of a sudden had a hearing among the political elites, why they wanted to entertain the possibility of him running for office, because they were afraid of this oppositional movement. So Badillo rode that wave and didn’t give enough credence or recognition to the fact that he was really riding a wave that wasn’t created by the political establishment.”

Badillo’s many failed runs for mayor seemed to reveal that despite his seemingly strong potential and presence, he never discovered how to capitalize on both his natural constituency and the political moment he found himself in. On the other hand, some feel he was sabotaged because despite efforts to mainstream himself, he was still viewed as an outsider.

“I think he’s the best candidate we’ve had in terms of credentials,” says Gerson Borrero, the long-time columnist for El Diario-La Prensa, New York’s most prominent Spanish-language daily. “I think he never got away from the fact that he was Puerto Rican, and I put that into the context of the allegedly inclusive Democratic Party, which practiced a blatant exclusion of Latinos. But he made headway.”

1977 Democratic Mayoral Primary:

Badillo Trails Crowded Field

2001 Republican Mayoral Primary:

The Last Hurrah

The next wave

Part of the new nationalist identity that Badillo rode was nurtured by an organization called Aspira, founded by a pioneering Puerto Rican educator and activist named Antonia Pantoja. Aspira was established to address high dropout rates and lack of educational achievement among Puerto Rican youth, and its stated goals were to encourage cultural self-awareness and critical thinking. Among the early student standouts in the New York chapter of Aspira was Fernando Ferrer, who, as a high school student, was vice president of the Aspira Clubs Federation. “I was very lucky to have been mentored by Toni,” says Ferrer.

Ferrer is emblematic of a generation of New York-born Puerto Ricans who came of age in the 1970s—his parents were working class, he was nurtured by Aspira during an era of national liberation movements, and he got a college education (at NYU). But unlike the more leftist activists of his generation, he became a classic machine politician in the Bronx, barely escaping being tainted by the Stanley Simon scandal in the 1980s to become a City Councilman and eventually borough president.

After an unblemished, if unspectacular run as Bronx borough president—critics contend that he was not so much responsible for a Bronx revival as its custodian—Ferrer then spent many years trying to re-forge the African American-Latino coalition that succeeded in electing David Dinkins mayor. He was hurt in 1997 by Dinkins’ endorsement of Ruth Messinger in that year’s primary race and dropped out soon thereafter, running instead for re-election to Bronx Borough Hall.

He came closest to being elected mayor in the tumultuous campaign of 2001. His Two Cities campaign made strong headway with New York voters, reflecting the under-acknowledged reality that working and middle class residents had not done as well under the ‘80s and ‘90s Wall Street boom as the white-collar finance world. Yet Ferrer felt as if many New Yorkers were not ready to hear the message.

“Mario Cuomo could talk about the Shining City on the Hill and two Americas, but when I said this about New York, people went bananas!” he laments. “It’s the same commentary, it’s about economic justice, and it was working and that’s what made people nervous.”

A race reshaped

While his economic critique made some editorial boards nervous, his hard-won endorsement from Rev. Al Sharpton was used to alienate white voters. Yet he was ahead in the polls when the 9-11 attacks canceled the original primary, then won the rescheduled primary—but only with 36 percent of the vote, less than the 40 percent required to forestall a runoff with Public Advocate Mark Green. In the brief run-off campaign came an infamous New York Post cartoon depicting Ferrer kissing Sharpton’s backside and a swirl of questionable race-baiting.

2001 Democratic Mayoral Primary:

A Short-Lived Triumph

“Somebody will tell me you know if it weren’t for September 11th you would have been mayor,” says Ferrer. In his book Contentious City, John Mollenkopf makes the argument that Green leveraged the shift in voter attitudes following the 9-11 attacks in his favor. While the Two Cities argument had given Ferrer a 36,000 vote lead over Green in the re-scheduled primary, Green not only questioned Ferrer’s ability to “rebuild the city” in the wake of the attacks, but came down on the side of Mayor Giuliani’s request to extend his term by 90 days.

“I said no to Giuliani, knowing it would cost me and open me up to attack,” says Ferrer. “I just couldn’t do it. Those are gut check moments.”

But race loomed very large in Green’s ultimate defeat of Ferrer in the runoff by a mere 16,000 votes. “Minority candidates will not win if non-Hispanic white voters feel those candidates will be representing non-white people,” says Hunter College Politics professor Carlos Vargas. “In Los Angeles, Villaraigosa was able to go beyond that, but so far no one in New York has.”

2001 Democratic Mayoral Runoff:

Ugly Race, Tight Finish

Green then failed in the general election against the deep-pocketed beneficiary of the restoration of Giuliani’s image, Michael Bloomberg. According to Mollenkopf, “Bloomberg’s areas of support coincided with those that had provided the votes for Green to beat Ferrer in the runoff primary. Clearly, many ‘Giuliani Democrats’ had voted first to help Green thwart Ferrer and then to help Bloomberg defeat Green.”

Long odds and shortcomings

Four years later, Ferrer again triumphed in the Democratic primary, this time narrowly achieving the 40 percent necessary to avoid a runoff. But there was little feeling of triumph as the general election loomed. Bloomberg was far ahead in the polls and had unlimited cash on hand. Outspent 8 to 1, mocked by the tabloids and abandoned by some Democrats who endorsed the powerful incumbent, Ferrer lost in the general election by a quarter of a million votes.

Ferrer’s achievement of winning the nomination in 2005 should not be diminished, but it should be seen in the context of a political world where incumbents are seen as increasingly difficult to defeat and candidates from the opposing party often wait until term limits oust an incumbent to mount a serious run—in a way Ferrer served as a sacrificial lamb in 2005, a chance for relative unknowns like Gifford Miller and Anthony Weiner to learn some citywide campaign chops.

2005 Democratic Mayoral Primary:

A Latino Nominee

2005 Mayoral General Election:

Landslide Loss

But Bloomberg wasn’t Ferrer’s only problem. Although he emerged on the public scene during a nationalist era, he was often perceived as being a machine politician who failed to take strong stands. Ferrer has often hedged his bets on the issues and his own identity. On gay rights he has both heartened and upset activists with seemingly contradictory stances. He went back and forth over the death penalty; he got arrested to protest the 1999 Amadou Diallo shooting but in 2005 told a police union audience that he didn’t think the killing was a crime.

Echoing Badillo’s chameleon strategy of pronouncing his name Ba-dillo (to rhyme with “pillow” rather than “Rio”) to make himself sound Italian, Ferrer was known to switch his name from Fernando to Freddy depending on the ethnicity of the crowd he was speaking to. His identity as a light-skinned Hispanic who emphasized his Catholic background played well in a Bronx with a substantial white ethnic population. In fact his adoption of the Two Cities campaign was seen as an unexpectedly strident move, albeit one that worked well for him until the political climate changed after 9-11. He returned to those themes at the end of the 2005 race—too late to make significant noise.

Moisés Pérez, a Dominican leader in the city who managed Rangel’s re-election campaign this summer, alludes to Ferrer’s incompleteness as a candidate when he muses about what it would take for someone to break through the barrier Freddy could not. “When we get a Latino candidate who is able to articulate a vision for the city of New York that is compelling enough to draw in all the critical players in the Latino community,” says Pérez, “then we’ll see a Latino mayor.”

This is the second in a five-part series. To read part one, please click here.To read the next chapter, clikc here.

Sources for the election results data include the New York City Board of Elections, Encyclopedia of the City of New York and Wikipedia.